If you were to put together a wall calendar of famous directors, there is little doubt that October would be reserved for the Master of Suspense himself, Alfred Hitchcock.

Over his six-decade career, Alfred Hitchcock directed more than fifty films, hosted and produced a long-running television anthology series, and was responsible for creating the language of the cinematic suspense thriller. It’s been more than forty years since he passed, but his influence is still widely felt. Let’s look back at some of the films of the past year or so that owe a debt to Hitchcock’s innovative approach to storytelling.

We’re Ready for Our Close-ups

Throughout his career, Hitchcock persisted in championing new technologies and techniques. He invented the disorienting dolly zoom (also known as the Vertigo Zoom, after the first film where he used it), and he wasn’t averse to cut-cut-cutting a scene in order to achieve the pacing he wanted. Psycho‘s shower scene — which made heated glass doors in bathrooms all the rage, by the way — consisted of 78 camera setups and 52 cuts. Alexander O. Philippe put together a documentary (called, as you might expect, 78/52) about these 45 seconds of film, which is a master class in pacing, misdirection, and suspense.

It’s all about moving the camera, you see, creating split-second grabs of our attention. Zooming in. Cutting away. Faltering into odd angles. Long tracking shots that pull away very slowly.

All of these techniques are on display in Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness. Sam Raimi, who cut his teeth in indie horror filmmaking before getting a shot at the big-budget spectacle film, has an idiosyncratic style that is clearly born of watching a lot of Hitchcock at a formative age. Close-ups of eyeballs, distorted frames, sudden zooms, and fractured images lend a sinister air to what is, ostensibly, a tentpole superhero movie.

Raimi knows that his audience is very familiar with a lot of the modern CGI tricks (case in point: the necrotic zombie version of Dr. Strange), and we expect a bit of flash and sizzle. But Raimi doesn’t rely on digital additives to carry his story. He goes back to the physical camera tricks that were Hitchcock’s bread and butter for creating suspense.

It’s All Part of the Lexicon

In some ways, it’s difficult to talk about modern filmmaking without acknowledging Hitchcock’s influence on the form. Everything from pacing to camera angles to the creeping sense of dread that pervades films like Alex Garland’s Men all go back to techniques and practices first established by Hitchcock.

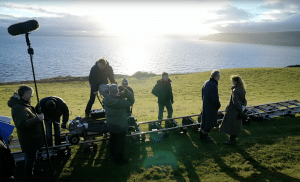

Men opens with a young woman named Harper Marlowe (played with a steely fragility by Jessie Buckley) arriving at a country house. She’s left the city for some reason (which is hinted at in the first moment of the film and which becomes abundantly clear through a series of flashbacks), and her stay in the country is meant to provide some space to process what has actually happened. And we, the audience, would like to know, too, but Garland isn’t going to tell us right away. This is Hitchcock’s first rule, after all: suspense before surprises.

And the surprises do come in Men. Harlowe’s lovely walk in the countryside is interrupted by a shadowy figure at the end of a long tunnel, and then she stumbles upon a naked man in an abandoned farmhouse. Things get weird from there, and over the next hour, we question whether Marlowe is losing her mind or she’s stumbled into a strange horror story out of country folklore. No amount of delicate piano work in the soundtrack and lush pastoral shots can erase the persistent dread that keeps haunting each frame.

And as for the ultimate surprise, well, that last half hour takes a turn, doesn’t it?

The Birth of the Cool

After innumerable COVID-related delays, we finally got to see Daniel Craig‘s final outing as superspy James Bond in No Time to Die, the twenty-fifth Bond film and the first to be directed by Cory Joji Fukunaga. Fukunaga kept us all rapt with his pacing and attention to atmosphere with the first season of True Detective, and he brings that same look and feel to No Time To Die. Locations glide by like glossy vacation wonderland TV advertisements. Characters are dressed for fine dining, not for high-stakes shootouts in Cuban nightclubs. The world is amazingly color-corrected and filled with expensive toys. And Bond? Even as battered as Craig’s Bond gets, he always looks utterly composed and unflappable.

There’s a plot, of course, and it gets thoroughly byzantine and nonsensical by the last hour, complicated by a MacGuffin or two. But it’s working from the playbook developed by Hitchcock for North by Northwest, his 1959 thriller starring Cary Grant and a crop duster.

The Bond franchise started in 1962, by the way, and sixty years on, they’re still using the cinematic language invented by Hitchcock. Sure, the cars are flashier, the clothes are sexier, and the icy temptresses are even icier, but it’s still Hitchcock at its core.

Looking for MacGuffin

And speaking of MacGuffins, has anyone actually ever seen one? The term was popularized by Hitchcock to represent the object (or idea) in the movie that the audience was invested in, but which was merely a device within the film that moved the plot along. The suitcase in Pulp Fiction, for instance. The Ark of the Covenant in Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark. The porno film in Ti West‘s X.

In West’s homage to a classic of a different sort (The Texas Chain Saw Massacre), a group of young people rent a barn at a remote Texas farm in order to shoot an “arty” porno film. Naturally, the couple that live on the farm take offense to all that wickedness happening in the barn and much carnage ensues. West even offers a scene where the earnest screenwriter talks about the concept of the MacGuffin in a sly wink-and-a-nod to the audience, but even this reference to a thing that isn’t a thing while talking about a thing that isn’t what we’re watching sort of thing is merely West doubling down on Hitchcock’s obsession with voyeurism and morality.

We like to watch, and Hitchcock leaned into the murky morality of our secret obsession with Rear Window, Hitchcock’s 1954 film starring James Stewart and Grace Kelly. Stewart’s character is a professional photographer who is recuperating from a broken leg. Confined to a wheelchair, he spends his days snooping the neighbors in his apartment complex. Naturally, he sees something he shouldn’t, and all sorts of complications ensue.

In X, West uses the pornographer’s film camera, views from a variety of windows, and even a set of peep-holes in the barn wall to put the audience in the point of view of characters in the film. We see what they see, and we feel what they feel. We’re just as responsible for what happens as these characters are. By providing us with this POV shots, West (and Hitchcock) are creating suspense, dread, and tension in the audience. We should probably look away, but we don’t.

Listening In

Stephen Soderbergh, working from a sharp script by David Koepp, turns this voyeurism on its ear, so to speak, with Kimi, a film about a woman who hears something she shouldn’t. Angela Childs (played like a spring wound way too tight by Zoë Kravitz) suffers from agoraphobia, and she works from home for a company that monitors data streams from a new smart device named Kimi. During a routine examination of a recording from Kimi, Angela hears what she thinks is a violent sexual assault. When she reports this to her supervisors, things go awry. Soderbergh, whose entire filmography is replete with all sorts of Hitchcockian influences, is clearly riffing on both Vertigo and Rear Window here, but Koepp’s script plays like an updated homage, demonstrating that Hitchcock’s core principles are still very vital.

Hitchcock wasn’t as concerned about plot as he was about characters. He wanted to understand what would happen to everyday people when they made one bad choice. How badly would their worlds spiral out of control? What other choices would they now make in an effort to save themselves? And how would the audience feel about this journey? Would they look away? Would they keep watching?

“I have a feeling that inside you somewhere,” Hitchcock once said, “there’s somebody nobody knows about.” Perhaps Hitchcock, and the directors who continue to explore the techniques he pioneered, know more about us than we do. Something to think about this month when the nights get longer and the shadows get deeper.

Cover image by CBS Photo Archive.

Looking for some more music for your projects? At Videvo, our library has everything from free ambient music to music for streams — perfect for any indie project:

- Royalty-free Christmas music

- Royalty-free meditation music

- Royalty-free upbeat music

- Royalty-free jazz music

- Royalty-free Halloween music

Need a break? Check out our videvoscapes — the ultimate reels for relaxation or concentration. Each videvoscape collects hours of high-definition nature footage and background video with downtempo chill beats for the ultimate escape from the grind.