The future arrived in the ’80s, so let’s take a look at the visual aesthetics that were born there.

The 1980s were a decade filled with technological innovation, Cold War paranoia, and padded shoulders. New Wave was sweeping the shores, and we were regularly blinded by science. It was a time of neon zig-zags, Art Deco implacability, and fever dream filters. Computers became personalized, special effects became magical, and filmmakers starting envisioning the future. It’s a strange decade of big hair, polyester plaids, and slick futurism. And the center of it all are the Scott Brothers: Ridley and Tony.

Big Brother

The older of the two, Ridley, was part of the British ad invasion of Hollywood, and in 1984, Ridley’s commercial for the Macintosh computer introduced the world to the idea of computational power on the desktop and in the studio rack. Computers weren’t just for theoretical physics departments and defense infrastructure. You could make bleeps and bloops in your own home, and over the course of the decade, our fascination for the possibilities afforded by portable devices bloomed.

Scott’s commercial also gave us a glimpse of a grim, meathook-style future of riot police, somnambulant drones, and decrepit granddads haranguing us from oversized video screens. It was a monochromatic version of the stylized future that Scott had recently brought to life with Blade Runner in 1982. We’ve spent the last forty years trying to avoid this future. Even Atari is back in business.

Scott’s output during this decade — Blade Runner, the Apple commercial, Legend, Someone to Watch Over Me, and Black Rain — are a master class in neon, rain, and practical effects. Even as the wizards at Industrial Light & Magic start doing more magic than lighting, Scott sticks with physical environments that can be controlled. Legend, for instance, an utterly fantastic fairy tale story about a boy, a demon, and a unicorn was filmed totally indoors. Those trees you see on-screen are sixty-foot tall props, and all those floating petals and pollen on-screen? Yeah, totally blown in for the shot.

The Classic Cut

Younger brother, Tony, makes two films in the ’80s: The Hunger — a stylish vampire film staring Susan Sarandon, Catherine Deneuve, and David Bowie — and Top Gun, a little film about fighter jets that starred a young actor named Tom Cruise. One embraces the fetishization of physical beauty and the all-consuming appetite for adoration; the other is a film about going really, really fast.

Catherine Deneuve’s Miriam Blaylock is a quintessential icy socialite with the masked marble that hid her true face from the world, the sort of woman who turned up every month Playboy as a Patrick Nagel illustration. Her clothing was angular and perfectly draped, the sort of attire one sees on a statue more so than a real body; the fabrics were luxurious and inaccessible to the common man. Contrast her with Susan Sarandon’s Sarah, who wore T-shirts and the simple single color attire of a working scientist.

Makes you look at Rachael — Sean Young‘s replicant character in Ridley Scott’s futuristic Blade Runner — in a different light, doesn’t it?

Top Gun, on the other hand, is all about sweaty bodies and the pursuit of individual excellence — sometimes at the expense of those around us. If The Hunger was an exercise in exploring what we do in the shadows and under silk sheets, Top Gun unabashedly embraced the naked exclamation of the ego. The unbridled thrill of “going for it” and “being the best you could be.” The only special effects in Top Gun were the assortment of filters Scott used to marble natural light into distinct bands of color.

Filled with Light & Magic

Meanwhile, a couple of films by a man named George Lucas changed the cinematic landscape forever. The Empire Strikes Back (in 1980) and The Return of the Jedi (in 1983) both showcased effects work done by Industrial Light & Magic. Practical effects weren’t good enough for space battles and forest fights with chubby teddy bears. In order to realize these visions, ILM had to figure out how to cheat the eye and combine computer graphics with filmed footage. And while Lucas’s pal, Steven Spielberg, would continue to make films the old-fashioned way for another decade or two (and do them well, by the way), it was young upstarts like Robert Zemeckis who were pioneering the use of computer-generated imagery.

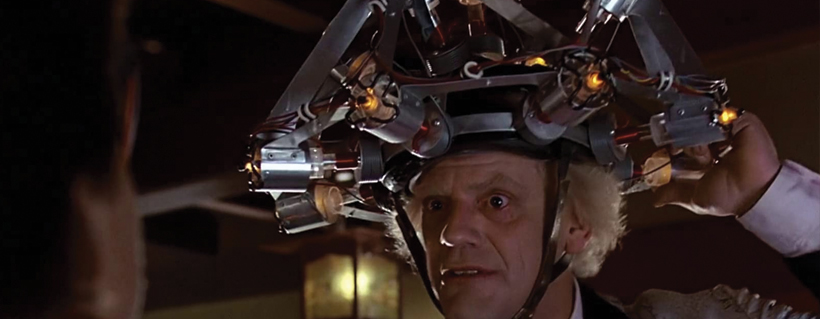

Zemeckis gave us Back to the Future in 1985, a film that is both a situational comedy about the nostalgia of coming into our own as well as a humorous speculation about the ripples caused by our decisions. While the film’s time-loop science fiction is played for laughs, behind the camera, Zemeckis was deeply involved in making the tools of the future work for him today. Zemeckis would make two more films in the franchise, both of which would become increasingly reliant on computer effects. But it’s the rest of Zemeckis’s oeuvre that reveals how deeply the film industry would embrace computer-aided special effects: Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), Death Becomes Her (1992), Forrest Gump (1994), and Cast Away (2000). After that, it’s The Polar Express, Beowulf, and A Christmas Carol — three films that pioneered motion-capture, thereby showing James Cameron that Avatar was possible.

Anyway, the reason Zemeckis is such a trail-blazer is because he understood that practical effects and on-screen chemistry were the foundation you put fancy window dressing on. Audiences showed up for story and eye contact between the leads. All the gee-whiz Technicolor artifice in the world won’t save you from a stale script.

And yet, somehow, Hollywood keeps making Transformer movies.

Deckled and Popped

When the ’80s were trying to invent the future, they were embracing the radical experimentation and funky angles of the “New Wave,” the latest group of musicians coming out England, who were delighting in geometric designs and contrasting patterns. It was a time of padded shoulders and long drapery. Triangles and rhomboids were everywhere, and the color palettes were either extremely neon or delicately washed out. The women all wanted to look like Patrick Nagel’s art and the men all wanted to dress like Don Johnson in Michael Mann’s Miami Vice. And Jan Hammer is the one providing the soundtrack.

In your own projects, evoking the ’80s means using your modern tools to dial in something from forty years ago. Contrast and pop were our big takeaways here — be it color, light, or characterization. The ’80s went big in every way, so your project should, too. And to get some of that magic lighting out of Top Gun or that magic from Legend, soften the edges of things a bit. Everything wasn’t so stark and crisp, cinematically speaking, back in the ’80s. Embrace a little haze, and your ’80s will come off like a dream.

Cover image via The Hunger (MGM).

Looking for filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out our YouTube channel for tutorials like this . . .