Let’s explore the distinctions of sound design and how filmmakers can use them.

As we discussed in one of our previous Think Like a Director pieces (Music Makes the Mood), a film’s soundtrack can do a lot of the heavy lifting to convey a film’s tone or mood. In most cases, this soundtrack is an artificial construct: it doesn’t exist within the film itself. Even when a Hans Zimmer soundtrack makes us feel all soft inside about a character’s introspective consideration of a familial sacrifice, inside the film, the characters aren’t getting this same level of emotional support.

The Layers of Listening

Except when they are, and that distinction is the difference between diegetic and non-diegetic sound. Okay, definition time: “diegesis” is a Greek word that means “the telling of the story.” It’s a fancy way of encapsulating the entirety of a story by way of a narrator who runs us through all the events and adds necessary commentary (i.e., the filmmaker). “Diegetic” elements are things within the contained universe of the story; “non-diegetic” elements are elements external to the story, but still connected to the story.

Deckard‘s much-maligned voice-over in first theatrical release of Ridley Scott‘s Blade Runner is non-diegetic, for instance, because the words are mouth noises that the audience hears, but which aren’t heard by the characters within the world of the film.

Why is this distinction important? Because diegetic sounds — sounds heard within the filmic universe by the characters within that universe — are elements which the characters can react to. Non-diegetic sounds are elements that the audience can react to. Think of that old adage writers get told all the time: “show, don’t tell.” “Telling” is non-diegetic, for the most part. “Showing” allows the audience to inhabit the film more completely.

The Art of Hearing Noises That Aren’t There

Take Quentin Tarantino‘s use of David Bowie‘s “Cat People (Putting Out Fire)” in Inglourious Basterds. As Shoshanna (played with a searing incandescence by Melanie Laurent) prepares to turn her Parisian theater into a Nazi-killing abattoir, the audience hears Bowie singing “Putting out the fire / with gasoline!” We completely understand what’s going through Shoshanna’s mind, even as she appears calm and directed. In fact, we can readily imagine her putting this record on while she applies her makeup.

Except . . . Inglourious Basterds takes place in 1944. “Cat People (Putting Out Fire)” wasn’t written until 1982. In fact, it was composed for a completely different film: Paul Schrader‘s erotic thriller Cat People. If Shoshanna had pulled this record out of a sleeve in Tarantino’s film, it would have ruined the audience’s investment in the film. By using the song in a non-diegetic way, Tarantino gives us a powerful insight into her character by using music from our own era — music that we have our own associations and attachments to.

Shonda Rhimes uses this same twist with the incidental music in her Netflix series, Bridgerton (based on a series of historical romance novels by Julia Quinn). Set in Regency era London, Bridgerton follows the various siblings of the titular family as they negotiate the highly competitive world of English mannered society. Throughout the two seasons, there are a variety of fancy dress parties, all of which have small orchestras providing “mood music.” Instead of relying on period-relevant music, the show’s composer Kris Bowers crafted orchestral covers of modern pop songs, from the likes of Ariana Grande, Alanis Morissette, Nirvana, and Billie Eilish. While these songs are all anachronistic to the time period, their diegetic use is cleverly disguised by rendering them in period-acceptable instrumentation.

Trans-Diegetic Sounds

And then, of course, we have trans-diegetic sounds. These are soundtrack elements that begin in one space and move into the other. For instance, David Leitch opens Atomic Blonde with New Order‘s “Blue Monday” as British operative James Gascoigne flees from an unseen pursuer. The song is clearly a non-diegetic soundtrack for the audience as Gascoigne runs down an alley, jumps a fence, and is struck by a car. However, when the driver of the car opens the door, the song is heard coming from the car’s radio. Suddenly, the music is diegetic, and yet, when Gascoigne is dumped in the river, the splash from his body neatly punctuates the end of the song.

That’s fairly clever, but it’s child’s play compared to Leitch’s use of George Michael‘s “Father Figure,” which Charlize Theron‘s badass spy Lorraine uses to cover up the sounds of a tussle in Gascoigne’s apartment.

When Lorraine realizes the cops are coming, she slaps a tape into the stereo and cranks the volume. We hear a split second of “Father Figure” blaring out of the stereo in the apartment before Leitch cuts to the hall outside the apartment, where the volume of the music is muted through the walls. We then cut to the framing narrative of the entire film (Lorraine’s post-assignment interrogation back at MI-6), and as her handler (played with English punctiliousness by Toby Jones) peevishly asks a question, we still hear the George Michael song. It’s suddenly non-diegetic.

During the fight sequence that follows, the song remains firmly diegetic: louder, when in the room with the stereo; muted, when in other rooms. Eventually, Lorraine makes her escape by leaping from the third floor balcony. The music fades as we move far away from the apartment, but then, after she dispatches two more policemen in the courtyard, we are treated to the final seconds of the song, where Michael delivers the last line without any backing instrumentation. And we’ve gone non-diegetic once again.

To Be Heard or Not Heard Is Truly the Question

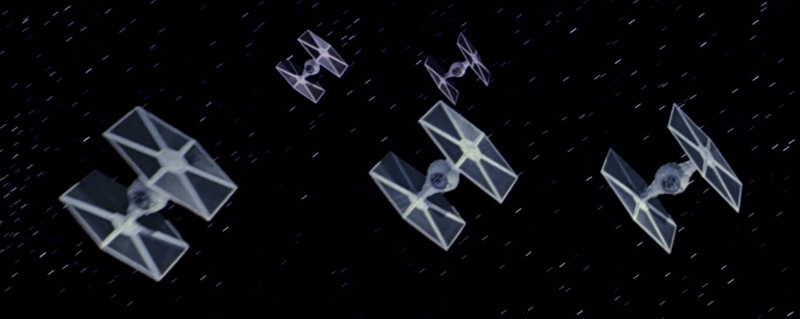

One of the most widely used non-diegetic sound design elements is sounds in space. While Stanley Kubrick widely eschewed diegetic sounds during the space sequences in 2001: A Space Odyssey, he used quite a few non-diegetic soundtrack elements to provide aural accompaniment to scenes that took place in a vacuum. Ten years later, George Lucas opened Star Wars with a scene of an Imperial Star Destroyer blatting and squirting laser fire at a Rebel starship over Tatooine. Throughout the film, T. I. E. Fighters howled as they coursed through space, and, of course, the Millennium Falcon rocked the theater’s sound system when it made the jump to light speed.

In fact, Lucas’s non-diegetic use of sound in space became so prevalent throughout the industry and with audiences that when Rian Johnson didn’t allow sound to travel through a vacuum in The Last Jedi, audience thought the film’s soundtrack was broken.

The Power of Responsible Sound Editing

However you choose you implement your sound design for your film project, keep the distinction between diegetic and non-diegetic sound in mind. What sounds are primarily for the audience? What sounds are relevant and pursuant to the cinematic universe you are creating? How can you use music (or sound effects) to heighten your audiences’ understanding of the film without ruining the magic you’re creating?

(Dune cover image courtesy of Warner Brothers)

Looking for filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out our YouTube channel for tutorials like this . . .