Science fiction is one of the most popular genres across all media, but it’s commonly not labeled as such. Let’s explore what defines this critical genre.

Science fiction — as an umbrella term — is any fictional narrative that has a “made-up” element that can be, ostensibly, extrapolated from existing scientific knowledge; which is to say, the audience doesn’t have to take any part of the story on “faith.” That said, what constitutes “science” gets a little hand-wavy, and so let’s see if we can nail this down a little better.

A Definition, or Two . . .

If your story involves a dead body in a locked room and the investigation that follows, you’ve got a mystery. If that locked room is on the moon, it’s science fiction. Simple as that. The reason is the first doesn’t involve any extra narrative support for your audience to follow: it’s a story that takes place in the here and now, and all the world-building rules are rules everyone understands. As a filmmaker, you don’t have to take time to explain any of the world-building to the audience.

Set this film on the Moon, and you’re going to have to devote a modicum of attention to informing the audience how the moon is different from Earth, because that is going to be a factor in the resolution of the film. Otherwise, why set the story on the moon, right?

The critical point here is you ground your audience in the narrative. They don’t have to understand how everything works; they have to know enough to comfortably follow the narrative of them. Science fiction says “If you really want to dig into the details, it’ll all track.” Rather than fantasy, which says: “Hey, it’s magic. It’ll be internally consistent, but I’m going to gloss over the details. Don’t wait up thinking about it.”

For example, Sean Connery’s classic Outland, which is, on the surface, the story of a marshal who comes to a frontier town and cleans up the local ruffians, restoring order to the territory. It’s a classic Western setup that was a staple of cinema during the mid-twentieth century. What sets Outland apart from the others is that setting is Io, one of Jupiter’s moons.

A Tale of Two Elephants

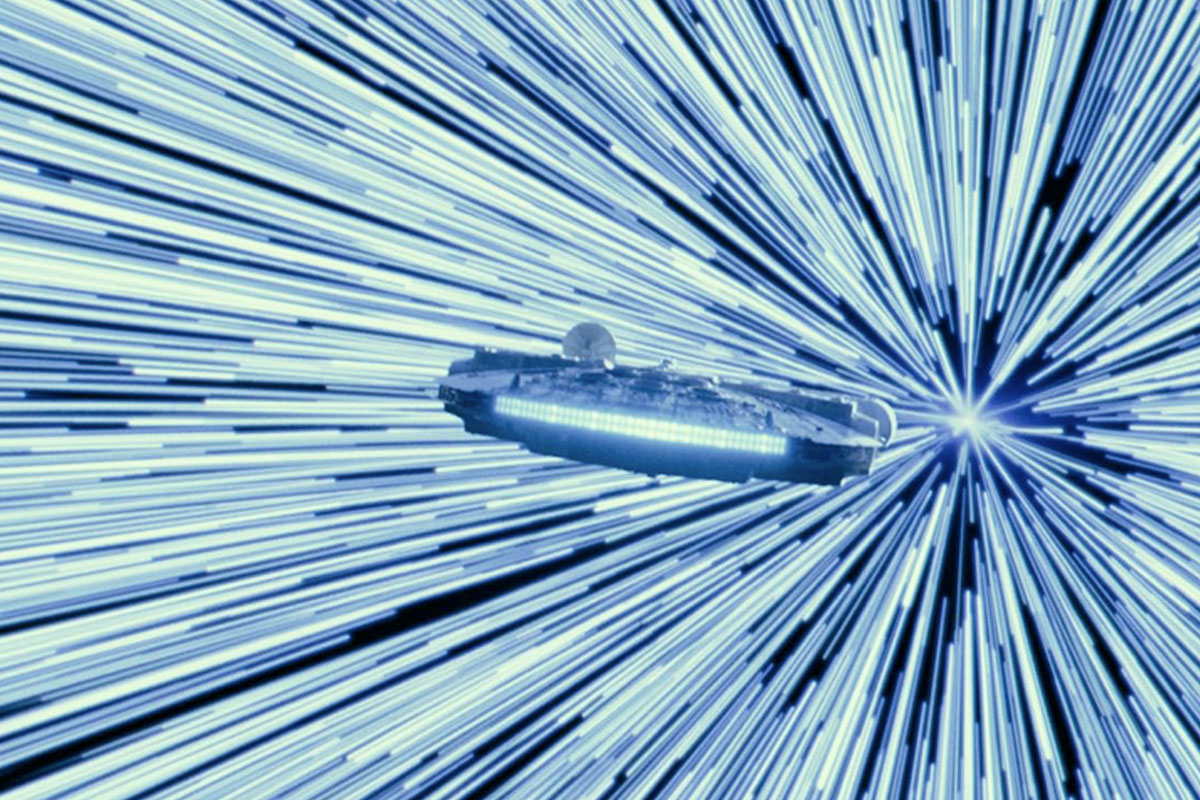

So, with that said, let’s turn to the two elephants in the room: Star Wars and Star Trek. Both are clearly science fictional, yet, they are radically different in their interpretation and exploration. Star Wars begins with the sort of phrasing one more commonly hears in an Andrew Lang fairy tale: “A long time ago, in a galaxy, far, far away.” It’s a polite way of saying: “Look, we’re going to make some things up now.”

And then we launch into a story of space ships, strange aliens, planet-destroying weapons, and arcana knights wielding swords of light. Oh, and the Force, which apparently surrounds everything and binds it all together, which is handy when you want choke someone across the room or, you know, astral project yourself across several thousand light years. So, yes, technically, you could use science to explain everything, but at some point, you’re going to run out of blackboard and these equations are going to look like you’re just doodling on the board on your way to a “Q. E. D.”

So, let’s call Star Wars “science fantasy,” or “Space Opera,” which is to say, stories told across large canvases, involving lots of drama and adventure. We’re not here for the philosophical discourse (Force-talk, notwithstanding) or the social commentary; we’re for the big set pieces and the mystic knights who are blocking enemy fire with the magic swords of light.

Star Trek, on the other hand, while it has many of the same trappings — space-faring vessels, strange aliens, relentless hive-minds that seek to devour everything — the shiny bits are in service of stories that are devoted to commentary and illumination of political, socio-economic, and cultural concerns that are happening now. Yes, these stories are set in the future, but they’re not really about the future. All these trappings are a way to critically talk about current issues through an illustrative lens. Science fiction is a “what if?” tool that allows a filmmaker to posit a world where some things are different and ask leading questions.

(A momentary aside concerning For All Mankind, Ronald D. Moore’s alternative history project for AppleTV+, which is the most literal science fiction property in recent history. Beginning with the Soviet Union reaching the Moon before the United States, the show explores an alternative history of the late 20th century, while maintaining a rigorous adherence to known science. A broad element of the show is still its commentary on the cultural and social issues that are relevant today.)

Put another way, you don’t have to squint too hard to see parallels to historical time periods and crises in Star Wars. If it feels like you’re watching a historical reenactment of the Industrial Revolution, but set it space, it’s probably Star Wars. If it feels like the world-building is an extrapolation of Ayn Rand’s Libertarian fantasy from Atlas Strugged, you’re probably watching an episode of Star Trek. If it has dragons in it, you’re . . . okay, you’re probably still watching Star Trek.

Science fiction is an extremely broad umbrella, and for the most part, Star Wars and Star Trek anchor either end of the curve. Where you fall in between is a matter of the filmmaker’s approach to worldbuilding and narrative focus.

Once Upon a Time . . .

Many argue that Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, written in 1818, is the first science fiction novel, with Dr. Frankenstein’s creation of life in the laboratory, but when you get into the details of Frankenstein’s methods, there’s a lot of hand-waving and alchemical talk about how lightning reanimates the monster, which feels like we’re veering into science fantasy territory, but Shelley’s story is all about mankind’s pride and hubris about their place in the Universe, i.e., commentary on the time in which she lives. That puts us back in Star Trek territory.

As we wade into the sub-genres of science fiction, we’ll constantly check ourselves against these two guides. Neither is superior; they are merely different foci of the creative effort. And this is how science fiction gets into everything: as soon as you suggest a “what if?” in your worldbuilding, you’re in science fictional territory. The rest is a matter of degrees.

The Harsh Future Is Upon Us

Dystopian science fiction stems from an extrapolation of a climate-based supposition. What happens when the oil runs out? Or when the atmosphere burns off? Or the seas rise? Films like Mad Max: Fury Road typify this science fictional starting point, along with fIlms like The Hunger Games, Divergent, and Mortal Engines. The question asked by the filmmaker is what sort of society persists in this sort of world? The recent reboot of the Planet of the Apes films are steeped in the same commentary and questions raised by Mary Shelley two hundred years ago.

On the other hand, we have Waterworld, which is basically Pirates of the Caribbean but set in a future where the seas have risen and we’re floating around on boats. Re-skin the past and blow things up. Sounds like the Star Wars side of the SF umbrella.

Monster Movies

Additionally, we should lump the giant monsters stomping on the cities of the world in this sub-genre as well. Godzilla, the original giant monster movie, was a reaction to the horrors of the atomic age, but it’s also a reaction to changes in the natural environment. Godzilla, and all the monster movies that came after, aren’t horror — not in the traditional sense — and they’re not purely science fiction, either. But they are both apocalyptic and dystopian — which is to say, climate-fiction suppositional — in their worldbuilding.

All Our Base Belong To Us

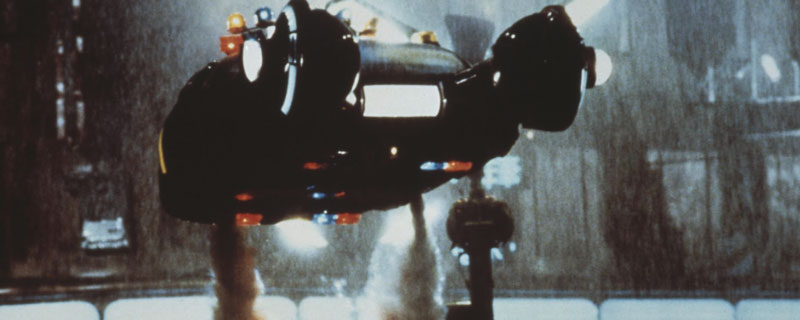

Another significant sub-genre of science fiction is the cyberpunk future, where the line between what is human and what is machine has blurred heavily. Films like Blade Runner (and its sequel, Blade Runner 2049) ask indelibly human questions against a backdrop of a climate-ravaged, post-economic collapse future. Due to our reliance on machines, are we more than or less than human?

There are films, of course, that do go neatly into any of these sub-genres. Take James Cameron‘s The Terminator, for example. Released in 1984, The Terminator walks and talks like a horror film, but the monster is a cybernetic killing machine from the future (okay, now we’ve got time travel, which is another category of science fiction), who has been sent back to alter the future, a future which is very dystopian in design. Is it cyberpunk? Is it climate-fiction? Is it a thriller with shiny parts? Is it social commentary (maybe not at the time, but now? You can’t swipe a mouse without getting helpful hints from AI tools, which some read as the precursor for Skynet, the murder machine that destroying humanity in Cameron’s vision of the future).

Is it a bird? Or a plane?

And we can’t talk about science fiction filmmaking in the 21st century without talking about superhero films. Much like Star Wars and Star Trek, superhero films can veer wildly from pure fantasy to arguable scientific extrapolation, and we can go so far into the weeds here that no one will find us. Let’s not stray too far. Superhero films are all based on a “what-if?” and that makes them science fiction. The rest depends on what the filmmaker is trying to accomplish. Is it gleeful escapism (see the first Guardians of the Galaxy film), or is it veiled commentary on social standards of our day (see, uh, the third Guardians of the Galaxy film)?

Ultimately, your film is science fiction as soon as you introduce an element of “what-if” worldbuilding. How deeply you want to lean on this supposition will shape how widely your film will be seen as science fiction, but treat this as the freedom it is: you’ve established that you’re going to make things up. The rest is entirely up to your imagination. To infinity, and beyond!

(cover image of The Millennium Falcon courtesy of Lucasfilm Ltd.)

Looking for filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out our YouTube channel for tutorials like this . . .