The ’90s are back, so let’s look at how to capture the visual and cinematic aesthetics that defined the decade.

The CD changed the music market in the mid-80s, and by the mid-90s, that same digital revolution had come to film. Even though the LaserDisc had been around since the ’80s, it never took off in North America, and once the DVD hit the market, LaserDisc never had a chance. We were still a decade away from the iPod, which would completely untether us from physical media, but for the last decade of the 20th century, we were all about the digital perfection offered by compact disc technology. We could watch films a thousand times and never worry about signal degradation again. We didn’t have to worry about the machines eating our media or our tapes wearing out. We could freeze frame in perfect clarity. We could inch forward, frame by frame, and obsess over every little detail.

Which meant film directors had to be that much more in control of every aspect of a film’s production. Light had to be controlled. Framing a shot became more than just having the stars hit their spots and spout their lines. CGI — computer generated imagery — was becoming a fundamental part of filmmaking, leading up to the virtual worlds created in 1998’s What Dreams May Come and 1999’s ground-breaking use of bullet time in The Matrix.

Dark Tones and Laser Beams

One of the directors whose filmography is a study in the application of technology to the 1990s is David Fincher. His debut was Alien 3 in 1992, followed by Se7en (in 1995), The Game (1997), and Fight Club (1999). Each movie showcased both a technological aspect of the ’90s as well as distinct visual aesthetic of the era. But before Fincher started making movies, he was a go-to guy for music videos. If you need a quick snapshot of the era’s visual vibe, all you need is a tour through Fincher’s videography. In fact, George Michael‘s video for “Freedom!” is a sublime celebration of the cinematic control a director can have in a digital environment.

I mean, just look at the opening. Linda Evangelista in a platinum bob with her icy blue eyes and blue eyeshadow. Blue laser beam hitting the shiny reflective surface of the CD — vinyl is so last decade, right? Black stereo equipment providing contrast with the blue-lit wallpaper. Fincher returns to this color aesthetic with the video for Aerosmith‘s “Janie’s Got a Gun” in 1994, and then dials up the blacks for the 1997’s The Game, a film that practically shouts its emotional unavailability with every frame.

It’s All Neon, All the Way Down

There’s a sequence in the middle of The Game, where Nicholas Van Orton (played with the intensity of a grenade about to go off by Michael Douglas) comes home to find that his house has been vandalized. The interior is trashed and covered with neon paint, a garish splatter of shocking pinks and yellows and greens. It’s meant to contrast the icy precision of Van Orton’s highly controlled life, but in the context of the decade, it’s the wild chaos of the rave aesthetic banging in through the back door and trancing out until dawn.

As the Internet began to provide global access to culture, fashion trends from Europe and Asia started to percolate through North America (and vice versa). American R&B act TLC stormed onto stage in the early part of the decade, and their street vibe was all about bright colors and floppy pants (in fact, they opened for MC Hammer, a man who knew a thing or two about pants, during their first tour).

Of course, by mid-decade, TLC was putting out videos that were totally working from the David Fincher playbook.

Mixing Your Palettes

This push and pull between the electric everyday of neon and the cold color palettes of money and power is on full display in The Mask, the film that launched Jim Carrey‘s manic career. The Mask, based on a comic book by Dough Mahnke and John Arcudi and published by Dark Horse Comics, was basically an attempt to create a vehicle for Jim Carrey to play a character who was a combination between a Tex Avery character and The Terminator. Along the way, director Chuck Russell got Industrial Light & Magic to showcase what this emergent CGI technology could do on the big screen.

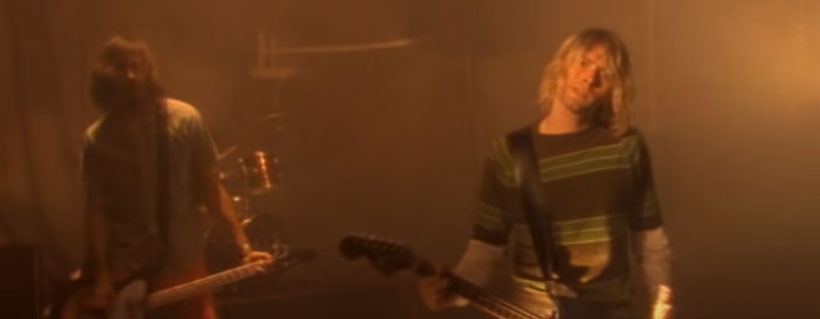

Grunge Is in The Air

The flip side to all this eye-popping color and floppy pants was, in a word, grunge. Nirvana’s Nevermind was released in 1991. Singles, Cameron Crowe‘s film about living the indie band life in Seattle, came out in 1992. By spring of 1993, everyone was wearing flannel.

If Punk was defined as an anti-fashion statement, then slouching onto stage wearing nothing more than an oversized stripper shirt, ripped jeans, and a pair of dirty Converse was about as punk as you could get. Hair sweat, cheap ‘n’ durable, and six days of separation from a shower was good enough to get us to the millennium. On the screen, that means exhausted color tones, a general haze in the air, and everything just a little out of focus.

The Verge of Unreality

Which brings us to Fight Club, David Fincher’s 1999 film. Aesthetically, the film encapsulates the entire decade. It is slick and perfectly color-corrected. Brad Pitt‘s character is the grunge poster boy for misplaced aggression. Ed Norton can’t figure out if he’s living in the real world or something born from his fevered imagination. Helena Bonham Carter is that dark Goth influence that haunted the shadows all decade. And throughout, from the flickering textual overlays to the subtle visual cues and subliminal suggestions, there is the ghost of CGI, the creeping influence of virtual reality.

A week after Fight Club came out, Spike Jonze‘s Being John Malkovich hit the screen. CGI wasn’t just for tent-pole action films anymore. Analog was gone; the world was going to be all digital from here on.

In your own projects, capturing all of these different ’90s vibes means experimenting. If Fight Club paved the way for metanarrative overlays and David Fincher taught us how to be afraid of the dark, then pulling a little from each of the ’90s mainstays is a great way to create that nostalgic feel. Slip the focus a little, play with strikingly bright and neon colors, and then just turn everything down a bit. We’re willing to bet you’ll nail the ’90s.

Cover image via Miramax.

Looking for filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out our YouTube channel for tutorials like this . . .

Looking for more tips and tricks? Check out these articles . . .