Reality gets pretty thin these days, and it’s no surprise that filmmakers have gotten creative with the documentary format. Here are some things to remember when making your own mockumentary.

Early on, you have to decide which approach you’re going to take with your mockumentary: play it straight or mug for the camera. The first is more time-honored, and it is a pure approach to crafting an imaginary nonfiction story. As a filmmaker, you keep yourself out of the narrative you’re building. The subjects of your film don’t break the fourth wall. If you provide voice-over narrative, it never intrudes into the film itself. It’s very true to the documentary approach.

So, let’s see this approach in action . . .

This One Goes to Eleven

The classic, of course, is This is Spinal Tap, Rob Reiner‘s tribute to hair-metal bands in the ’80s. Written with unflinching verisimilitude and an impossibly earnest innocence by Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, and Harry Shearer, This is Spinal Tap introduced the world to England’s loudest band, who also happen to be a trio of lads who are utterly unaware of how cliched their entire act is. Of course, it took less than a decade for Reiner’s film to transcend its comedic roots and become an indelible part of the hair metal band culture.

Making Eye Contact from Across the Room

At the other end of the spectrum, the subjects of the mockumentary know they’re being filmed. They’re in on the joke, so to speak, but as much as the “documentary” is about them, the “mockumentary” — the filmmaker’s larger vision of the project — is another layer entirely. Take The Office, for instance. Both the British and American versions of the television show are framed as a documentary about the daily grind that is working at a paper supply company.

The producers of the documentary make an effort to stage interviews with the staff of the company (and we rarely see the questions being asked, of course), and in both cases, the manager of the office mistakenly believes the crew is there to showcase his incredible talents at running the company. However, this individual is, frankly, an egocentric blowhard, who, all best intentions aside, may very well be the worst boss ever.

And it’s only through long-suffering fourth-wall breaking looks from the rest of the office staff that tell us that they, too, understand the joke.

Selling The Audience That Suspension Bridge

Both styles, of course, require a large suspension of disbelief on the part of the audience. Both are filled with actors who are working from scripts (though, the first style may lean more heavily on improvisation), and even when the actors appear to be breaking “character” by acknowledging the presence of the camera eye, they are merely acknowledging the cinematic presence of the film crew. They aren’t seeing us, the audience, even though their “can you believe this nonsense?” glances suggest otherwise.

Think of it this way: the first style confuses the audience. It tries to convince you that it is real — we want it to be true, don’t we?—even though it isn’t. The second knows it’s a lie, but with a wink and a nod, it says “You know exactly what we’re talking about, don’t you?” Its ludicrousness is false, but relatable because parts of it are true (though exaggerated — turned up to eleven, if you will).

The Blair Witch Project is an example of the first style, for instance. It wouldn’t have worked if the characters knew they were being filmed. Well, they were being filmed, but you know what we mean. The film works because it is framed as something that has to be OMG! true, and even though we know it isn’t, we want it to be. No, wait. We don’t want it to be true, because that would mean . . . wait. Was it true? The point is: it works because you believe it, not because you find it to be an exaggerated mirror held up to the real world.

Either/Or And Both, It Depends

Regardless of the style of documentary, remember that you are constructing a world that is just as real as our world. It’s not prettier or grittier or filled with incredible filters. You’re not Michael Bay or Tony Scott. Your camera work should be mundane, person-on-the-street style as you follow your subjects. Be present, but invisible (unless, of course, the camera is supposed to be part of the scene). Let your subjects tell their stories in their own way.

Christopher Guest, who understandably dislikes the term “mockumentary,” sets up the frame for his story and lets his actors tell it. The scripts are simple frameworks around which the actors improvise a great deal of their dialogue and interactions. The story emerges as the actors work through the framework. This model can be a little terrifying to visualize for a director, but Guest works with the same actors a lot, all of whom are fabulous improvisers. The results are stories about competitive dog training (Best in Show) a folk troupe preparing for a reunion performance (A Mighty Wind), a behind-the-scenes look at the world of sports league mascots (Mascots), and This is Spinal Tap — the rise and fall (and rise again) of the England’s daftest metal band.

It’s All True, Except the Bits That Aren’t

In all cases, what works is that the characters are all relatable. They are bundles of cliches that we know, that we see in ourselves and in others around us. These cliches may be exaggerated, and the degree of this exaggeration will undoubtedly mirror the style of documentary you’re shooting for. The magic trick of this format is letting the audience convince itself that what they’re seeing could be true. Keep them grounded in the world they think is the real one. The lighting won’t be good. Shirts will have wrinkles. People will miss a spot when shaving or forget to put their makeup on all the way. They’re just like us, remember.

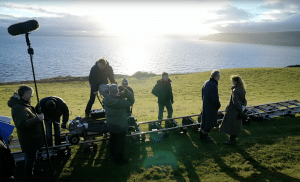

(Cover image via Embassy Pictures)

Looking for filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out our YouTube channel for tutorials like this . . .