In this write-up, we’ll take a look at what we mean when we talk about “action films.”

Look, every story ever told is a story of conflict. Whether we’re talking about a bunch of guys showing up on a beach to bang on the walls of a city over a pretty girl or we’re talking about one brother deciding he’s had enough of the other brother, the story is driven by physical action.

Honestly, it’s easy to watch. It puts butts on seats. It transcends language. Some, in fact, will argue you don’t even need dialogue for an effective action film (c.f. the number of lines of dialogue spoken by John Wick in each successive film). Conflict in an action film is the purest expression of conflict between a protagonist and an antagonist.

Things That Go Boom!

The earliest expression of an action movie is the war film. From outside the walls of Troy to the battlements of an English castle to the beach at Normandy, the war film has brought us the bone-crunching, arrow-thunking, battalion-crashing ferocity of combat. Back in the black and white days of cinema, it was easy to sort out the good guys from the bad guys with classics like A Bridge Too Far, Midway or The Guns of Navarone. While we know the villains by their uniforms or other markings, for the most part, they are faceless and anonymous. The antagonists in Top Gun: Maverick, for instance, are fighter pilots of an unnamed country who are only ever seen wearing masks and helmets.

As the emphasis in these stories shift to character-driven pieces, we see the action recede. Films like 1917 and All Quiet on the Western Front are very much war films, but the focus of the filmmaker isn’t the bang-boom of all the military hardware, but the impact on and damage done to the participants. Take, for instance, the sequence with the sniper and the church in Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan. The war between the Axis and Allies is reduced to a handful of soldiers locked in mortal combat.

High Plains Drifter

Action films that focus on a single individual fighting against a larger injustice came to the fore with the Western. These films are typically the story of a solitary wanderer who is talked into fighting a fight that isn’t his against an enemy he doesn’t know. The American Frontier was one of the essential backdrops for this sort of action film, and in post-WWII Japan, we see the rise of the samurai film. Armed with his trusty sword or six-shooter (or both, as in the case of Takashi Miike’s Sukiyaki Western Django), the steely-eyed loner was judge, jury, and executioner in a world where might triumphed over right.

While Hollywood definitely leaned into the tropes of the Western with directors like John Ford and Howard Hawks, it was Italian filmmaker Sergio Leone who tossed out the Manifest Destiny Westward Ho! rulebook and distilled the genre down to its core narrative structure with a trilogy of films starring Clint Eastwood.

The Action Hero

We should note there exists a moment in cinematic history when the Western grew up. That moment is when John McClane (played by a relatively unknown comedic TV actor named Bruce Willis) whispered “Yippee ki-yay” to euro-terrorist—sorry, gentleman thief—Hans Gruber (played with genre-defining aplomb by Alan Rickman) during a Christmas party gone horribly wrong at Nakatomi Tower. Die Hard brought the Western into the modern era, and since then, the solitary hero fighting a fight that isn’t his against an enemy he doesn’t know translates to “It’s like Die Hard, but . . .”

David Leitch‘s Bullet Train, for all its gonzo action and iconic characters, is basically “Die Hard on a Train,” but with more backstory. Brad Pitt‘s Ladybug is merely the wrong guy in the wrong place at the wrong time, and the film is him trying not to get sucked into a family feud that is leaving a lot of bodies in its wake.

Shaken, But Not Stirred

Somewhere between the thunder of war and a New York cop scrawling “Now I have a machine gun” on a dead terrorist’s sweatshirt with lipstick, we find the clever hero who fights for a proper cause against an enemy that puts its own assassins in the field. The spy film comes in all sorts of gradations of Things Blowing Up, but since we’re focusing on action, we’ll reference the gold standard here, which are the films starring Ian Fleming’s infamous spy, James Bond.

Played by a handful of iconic leading men, the Bond films marry widescreen technological pyrotechnics with the scrappy efforts of an exceptionally well-trained asset. These sorts of action films typically take place in urban environments and typically have a narrative through line of geopolitical machinations that power the underlying narrative conflict. The Russo Brothers’s The Gray Man, for instance, is essentially a cat-and-mouse game between Sierra Six (played with stoic austerity by Ryan Gosling) and Lloyd (played with mustache-bristling fun-house glee by Chris Elliot), but the What-for? and Why-this? is driven by politically explosive office politics.

All Fun and Games Until the Roof Gets Ripped Off

And what do you get when the antagonist isn’t a group of radical separatists or a global power bent on creating a universal hegemony? What happens when the antagonist is an expression of natural force? Well, you get the disaster film.

There’s a subset here where the power in the narrative is the looming destruction of something manmade, but I’ll argue the antagonist in these films is still the natural world, aka physics. Gravity, for instance.

Regardless, the action in these films stems from the looming arrival of a destructive force that cannot be reasoned with. The protagonist, either working with others or by themselves (but in communication with others), must race against the clock to prevent total destruction. Along the way, of course, lots of things blow up.

A Long Time Ago, In a Galaxy Far, Far Away

So where does Star Wars fit in all this? Well, it’s kind of a military film (all those masked stormtroopers), but it’s also a Western (“the Force is strong in this one”). But come on, the Death Star certainly falls in the category of “destructive force that cannot be reasoned with.”

Since science fiction films (and fantasy films, for that matter) tend to be a mashup of history, mythology, and sheer make-believe, they also tend to blenderize the distinct action categories. Some of them cleave fairly close to the definition—Outland is basically “Shane in space”—but others, like most of the Star Wars and the Star Trek films, tend to mix-and-match as they see fit. And that’s okay. We can label this bucket accordingly.

It’s All in the Wirework

And since we’re letting one subset of films bend the rules, we should also acknowledge the efforts of Asian filmmakers. The broad category of “martial arts films” are definitely driven by and filled with physical action set pieces, but again, there are elements of the solitary hero roaming the frontier, the soul-grinding oppression of faceless overloads, and the frenetic efforts of spirited individuals to fight for the little guys.

See, the Seven Samurai gave us The Magnificent Seven which gave us Guardians of the Galaxy which gave us Dungeons & Dragons Honor Among Thieves.

It’s okay. There won’t be a quiz.

When you set out to make an action film, look beyond the staggering amount of pyrotechnics. For all its CGI-enhanced flash, action doesn’t happen without purpose. There’s a narrative line that pushes the audience through the action. That’s the soul of your film. The rest is, well, exciting to watch, but what elevates your film is the What-for? and Why-this?

I mean, John Wick spawned an entire franchise (four films, a streaming series, and at least one more film on the way) because of a single bad decision.

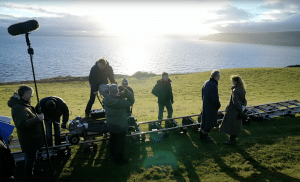

Cover image from John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum, courtesy of Lions Gate Films.

Looking for filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out our YouTube channel for tutorials like this . . .