Cinematographers use a variety of shots to tell visual stories. In this article, we explore one of the most common — the medium shot.

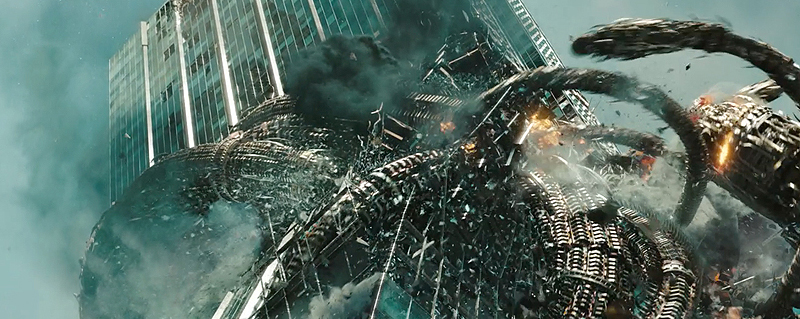

Shooting a film is both an exercise in creating a fully realized world and lying to your audience. Within the frame of the film, you have to convince your viewers they are peering into a complete world — a world that extends beyond the edges of what they can see. Sure, you can do a lot of with CGI these days, but effects can balloon your budget really quickly (Michael Bay’s Transformer movies, anyone?).

Filmmaking is the art of illusion, after all, and there’s a lot you can do with the medium shot. And the medium long shot. And the medium close-up shot. Let’s dig into what these are.

The Medium Shot, Defined

In the simplest terms, a medium shot is a composition wherein the subject of the frame is not dominating the frame. They are clearly the primary element of the shot, but the framing is wide enough that other elements of their environment are visible. It is, frankly, an ubiquitous shot, made invisible in many ways because it is so common. You can use it to establish the players in a scene, to show the environment where the scene takes place, to set the mood of the scene.

Roger Deakins, one of the great cinematographers working today, has collaborated with the likes of Sam Mendes, the Coen Brothers, Denis Villeneuve, Ron Howard, and Martin Scorsese, and his corpus of work is a master class in composing the medium shot. The image above, for instance, perfectly frames Daniel Craig (playing James Bond), tells you where he is in his environment, and sets a mood with the play of colors and shadows. Craig is shot from the waist-up. There are an equal number of like-colored elements on either side of Craig. His back is to us, and he is toasting the gentlemen on the balcony in the background — clearly establishing a depth of field. On his left, the martini is on the bar. His right hand is holding another martini. You only have to squint a little to read this as the Magician from the Major Arcana Tarot card.

Readying Ourselves for Our Close-up

When you dial the shot in a little tighter, you have the medium close-up. Here, your focus is more on the character themselves. We’re paying attention to their reaction, to their facial expressions, to the emotional beat of the story. We’re not as connected to the character’s relationship to the environment around them. In most cases, you frame the character from the shoulders up, giving them a little room to move around in the frame without the audience peering up their nose.

In Nope, Jordan Peele kept the audience wondering about what was hiding in the clouds by using medium close-up shots of the characters reacting to what they were seeing. It’s a powerful way to build tension and keep an audience engaged by leaving something to our imagination. We’ve come a long way from directors hiding the monster because it’s clearly a dude in a rubber suit (Ridley Scott with Alien) or a creaky animatronic that is always breaking down (Steven Spielberg’s shark in Jaws), but using the medium close-up reaction shot to heighten tension is a classic technique.

Painting the Landscape

The medium long shot is the opposite of the close-up. We still have our characters in frame, but they are not the dominant element. They are part of the landscape, and shots like this from Sam Mendes’s Empire of Light are used to ground the audience in the narrative. Use them to transition to another scene or to provide a narrative beat to a scene. You can’t do too much with character interaction or intense emotional reactions because the audience is just too far away to easily track delicate nuances in facial expressions.

We go back to Deakins again, who likes to frame these shots from the knees up. It allows us to stay a little tighter on the figures. In the early days of cinema, this also hid things like dolly tracks and other visible markers used by the crew to create the illusion of a realized cinematic world.

Of course, these days, practiced directors of photography like Hoyte van Hoytema bring in the Technocrane and a bunch of VFX guys, and suddenly, the magic is very real.

Objects in Motion Tend to Stay in Motion

Aaron Sorkin is known for dialogue-heavy scripts, and in many of the films made from his scripts, directors have framed scenes with medium-long shots and let the actors rapid-fire their lines back and forth. But Thomas Schlamme, Sorkin’s frequent collaborator on The West Wing, came up with a cinematic style of tracking shots through sets while the actors were barking out three or four pages of dialogue. This style became known as the “walk and talk,” and in any given shot, there will be multiple shifts between medium long and medium close-up as characters enter and leave the frame. It’s a tricky composition, but when it works, the filmmaker is able to accomplish a lot with an economy of frames.

Conversely, when someone like Kenneth Branagh wants to make a spooky thriller, he eschews his penchant for complicated tracking shots with jarring medium close-ups from odd angles. A Haunting in Venice, his latest outing as Agatha Christie’s famous detective Hercule Poirot, takes place over the course of one night in a palazzo that might be haunted. As bodies start piling up, the on-screen tension is played up through abrupt cuts, unconventional camera angles, and close-ups that are a little too close. These are the sorts of tricks used by Alfred Hitchcock and several generations of Italian horror directors, and they’re very effective at manipulating the audience’s reaction to scenes.

And that’s what all great filmmakers and directors of photography are doing when they squeeze something new out of the existing techniques. How you frame your shots sets the tone for how the audience is going to react to your film. Use your shots effectively to create emotional framing for your scenes. Bring us close when you want us to connect with the characters. Push us back when you want us to think about the bigger picture. This push-pull is the secret to elevating your film.

(Still from Argylle courtesy of Apple Studios)

Looking for filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out our YouTube channel for tutorials like this . . .