Every film is nothing more than a bunch of still images strung together. Let’s look at one of the oldest special effects used by directors: clay-based animation.

Early cinema was nothing more than a series of images that presented the illusion of movement (usually on some kind of rotating drum like a zoetrope), and these filmmakers pioneered the use of the stop-trick — adjusting the scene in an incremental way between shots to imitate real motion — to fool the viewer’s eye. String together a series of stop-tricks, and you’ve got stop-motion filmmaking.

Our brains process visual information at about twenty-four frames per second. Much faster, and we’re left with the nagging sensation that we’ve missed something. To effectively create a ten-minute film, you need a little over 14,000 shots. Even if you double-frame, a technique of exposing two frames for each shot, you’re still going to need more shots than you can reasonably expect a human actor to sit still for. Which led directors to find a medium that would be extremely malleable and yet not fussy. That medium would be clay.

Of course, clay, being highly mutable, was subject to vagaries of the environment. Too much heat, and clay faces start to melt. Too cold, and it became difficult to make the incremental changes necessary from shot to shot. Fortunately, in the last few decades of the nineteenth century, a German pharmacist and an English art teacher both created variants of an oil-based modeling clay which was much easier to work with. That leads us to The Sculptor’s Nightmare (1908), in which three busts bubble into shape and then harass a gentlemen who is convinced that he’s trapped in some kind of Dickensian nightmare.

For the record, the claymation portion of this short film is only two minutes of its nine-minute run. The director, Wallace McCutcheon Sr., was well aware of the limitations of his medium.

Early directors realized that stop-motion animation would allow them to create “larger-than-life” spectacles, and when combined with a number of clever cinematic tricks like rear projection and the Williams process of double matting, filmmakers were able to create King Kong, 1933’s classic that would introduce audiences to an entirely new genre of films—the monster movie.

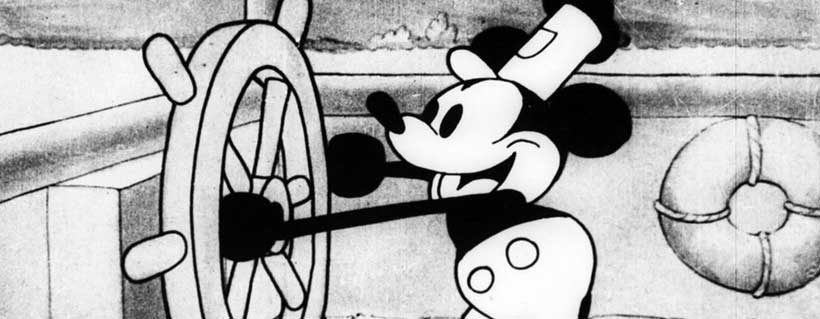

But it was an expensive process, and Walt Disney and his cartoonist pals had demonstrated that you could entertain audiences just as readily with cel drawings. And more cheaply too. It was much easier to farm out production of a cel-animated film to a team of artists than it was to divvy up the work on a clay-animated project.

It wasn’t until the 1955s when Art Clokey invented Gumby, a green clay humanoid with googly eyes, that claymation started to gain some traction. Gumby debuted on the Howdy Doody show, where he quickly captured the imagination of American television viewers. For much of the next decade, Gumby (and his pony pal, Pokey) were a mainstay of children’s TV programming. Eddie Murphy‘s brilliant parody of Gumby for Saturday Night Live in 1987 led to a revival and another ninety-nine episodes.

Of course, we’d be remiss to not mention Mr. Bill, who was a reccuring character on Saturday Night Live. Created by Walter Williams as part of a request for “home movies” during the show’s inaugural season, Mr. Bill would show up sporadically for the next few years, along with his dog Spot, who usually died horribly, and Mr. Bill’s nemesis, Sluggo.

Meanwhile, in the U.K., Peter Lord and David Sproxton (of Aardman Animation fame) were making Morph, a simple figure that mutates into all sorts of shapes and objects. Again, like Mr. Bill and Gumby before him, Morph was an interstitial character, usually showing up in short segments less than a minute long during the BBC’s Take Hart show.

Of course, Aardman Animation also gave us Wallace and Gromit, a series of shorts about a forgetful inventor and cheese-lover and his best friend, a dog who never says a word, but who always has lots of opinions about what is going on. The Wrong Trousers (in 1993) and A Close Shave (1995) both won Academy Awards for Best Animated Short, thereby elevating claymation to a cinematic art form. In fact, Aardman would go on to make a half-dozen claymation films, including Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, Shawn the Sheep: Farmageddon, and a pair of Chicken Run films.

We should take a moment and note that “claymation,” shorthand for clay-based animation, is a term that was used exclusively by Will Vinton for many years. Vinton and Bob Gardiner created a 3D animation technique that they used for their Oscar-winning short film “Closed Mondays,” which is a Twilight Zone-esque story of a drunk who wanders into an art museum late at night and experiences a number of surreal encounters with the art before becoming part of the installation himself. “Closed Mondays” was made in 1974, the year that Mr. Bill first appeared on Saturday Night Live.

Much later, Will Vinton Studios would become Laika, a Portland, Oregon based stop-motion studio, which produced Coraline, ParaNorman, Kubo and the Two Strings, and Missing Link, a series of films that would meld traditional clay-based animation with CGI, bringing the classic form into the modern era.

It’s easy to get distracted by all the technical complications of modern animation, especially when you add fluids and weather. (Aardman’s Flushed Away was entirely CGI, even though it has that classic Aardman clay-motion aesthetic, because water is hard.) But remember how it got started. Look at the classics we’ve mentioned in this article. Clay is mutable. Clay can become anything. Clay is a cheap special effect that will let you realize all sorts of strange worlds and odd stories. It’s old school DIY, which is still powerful when it is coupled with strong storytelling.

(cover image courtesy of Aardman Animations)

Looking for filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out our YouTube channel for tutorials like this . . .