The Western is all about taming the Frontier. Let’s unpack this cinematic genre and discover how deeply it is rooted in our psyches.

On the one hand, the Western, in its simplest expression, is one of the purest forms of American cinema. Soon after the American Civil War, the country began its largest period of expansion, as people rushed to fill what they saw as “uninhabited” land. This westward spread was buoyed by the befuddled idea of Manifest Destiny (the notion that “we’ve got to go over there and stick a flag in it because God told us to”), and for rest of the 19th century, Americans rushed to fill this vast, uncivilized land. The peoples that were already living there? Well, they were getting in the way of the spread of American ingenuity and commerce.

Westward, Ho!

The West was to be tamed, you see, and the only law that mattered was the law of the mighty. The American hero was a knight-errant, a privileged warrior who, with his horse and his rifle, had been tasked with a divine duty to protect the women-folk, defend the newly fenced-in ranchlands, and drive off those murdering interlopers (the, uh, actual natives).

This was the narrative that informed a series of traveling sideshows, most notably Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. These shows toured the established portion of the nascent United States, reiterating the newfound myths of the frontier. In fact, Buffalo Bill’s show was captured on film in 1904 by Thomas Edison and his team while they were exploring ways to create “motion pictures.”

Edison and his ilk were introducing all sorts of new-fangled technology to society, which folks found both fascinating and terrifying. This industrial “moderization” was oppressive, and they felt constricted and trapped within the new paradigm of urban living. In contrast, the vast emptiness of the American West was, in a word, freedom. Some of the technologies filling their lives with noise and smoke were, in fact, means by which they could escape, by which they could vanish into the mythology of the West.

The Bright-Eyed Adventurer

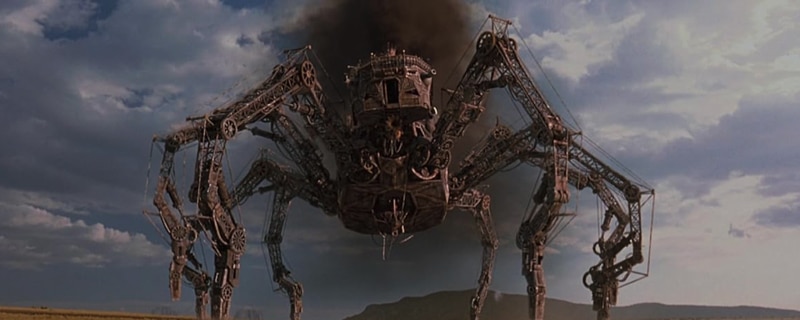

This brings us to the Edisonade, a genre of pulp fiction that featured a quirky inventor and his magnificent inventors. Together, they have adventures. The genre came out of the scientific romances of the Victorian era, and would later find itself spackled into the pulp foundations of science fiction. One of the earliest examples of this genre is Edward S. Ellis’s “The Steam Man of the Prairies,” published in 1868. It’s the tale of a young man with his—wait for it—steam engine that allowed him to chug-a-chug to various adventures in this mythological West.

130 years later, we have Will Smith and Kevin Kline fighting a diabolical Confederate scientist with a penchant for steampunking giant arachnids that spew jets of flame in Barry Sonnenfeld‘s Wild Wild West. Plus ça change, as they say.

American cinema in the mid-20th century perfected the essential format of the Western: a man, a horse, a rifle, and folks in need of justice. Directors like John Ford, John Sturges, Delmar Daves, and Samuel Fuller were in high demand during a period known as the “Golden Age of the Western,” which ran until the early 1960s. Actors like John Wayne, Gary Cooper, and Fess Parker became iconic heroes with their laconic drawls, Stetson hats, and fur caps.

Unspooling the Spaghetti

In Italy, Sergio Leone embraced the cinematic wide-screen vistas of the American West, and over the course of three films starring a stoic, steely-eyed American, both deconstructed and elevated the mythology of the genre. Leone’s films, shot in Italy and usually dubbed into English (the crews were a mix of European and American actors), became international hits and helped spawn an entire sub-genre (the “Spaghetti Western”).

Leone’s go-to actor was a young fellow who had gotten his start on Rawhide, an American TV western. He and Clint Eastwood did three films together: A Fistful of Dollars in 1964, For a Few Dollars More (1965), and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). While Leone only did one more Western (Once Upon a Time in the West), Eastwood went on to do a number of memorable westerns, including High Plains Drifter (his first time in the director’s chair, in 1973), The Outlaw Josey Wales, Pale Rider, and Unforgiven, his Academy Award winning deconstruction of his own career in the Western genre.

Sam Peckinpah, who had done a few Westerns himself, took Leone’s demystification of the Western one step further with The Wild Bunch, a film that did away with the doe-eyed filter of the American Individualism and showed us how bloody and lawless the frontier could be.

The Myth of the Lone Hero

Eastwood is also known for the character of Harry Callahan, a granite-chewing San Francisco police officer who, much like the unflappable heroes in Westerns, was prone to taking the law into his own hands. The first film starring Callahan was Dirty Harry, and it is widely seen as inaugurating the “loose-cannon cop” sub-genre, which, in a way, is basically a Western (single individual takes the law into their own hands in service of a community that cannot protect itself against Evil) set in a urban setting.

And herein lies the trap of the Western. It was certainly a staple of early cinema, especially given the broad reach of Hollywood throughout the 20th century, but that same wide availablity and broad representation of a specific historical and cultural milieu ignores how the underlying elements of this genre found expression in other cultures.

The Romance of the West

As we mentioned above, the gunslinger hero is an Americanized version of the knight from the chivalric romances of the Middle Ages or the wandering ronin from Japanese history. One of Akira Kirosawa’s most enduring films is Seven Samurai (1954), the story of seven swordsmen who are hired to protect a beleaguered village from marauding raiders. It would be remade by John Sturges in 1960—at the tail end of the Golden Age of the American Western—as The Magnificent Seven (and would be remade again in 2016 by Antoine Fuqua).

Why seven? Who knows. It probably goes all the way back to Aeschylus in 467 BC, who turned the mythological story of the few against the many into an hour of talking heads on stage. And with seven characters, you have the opportunity to cast a wide range of standard character types for a well-rounded dramatic narrative.

What’s New Is Old, and What’s Old Is New

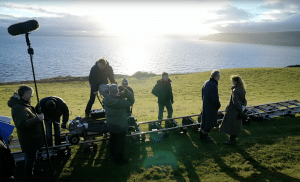

And when we disconnect the narrative elements of the Western from the historical baggage of the Myth of the American West, it’s possible to see a film like David Lowery’s The Green Knight (from 2021) as a Western, albeit in a highly stylized, experimental, “maybe this is all a metaphor” sort of way.

Westerns are fantasies, inasmuch as they are expressions of a world that never really existed—a world where destiny, staunchy individualism, and a steadfast belief that hope and decency will prevail—and they are, fundamentally, stories about people who take it upon themselves to improve the world around them, in whatever minute way they can.

They’re never just about a guy and his horse.

(Cover image from Tombstone, courtesy of Hollywood Pictures.)

Looking for filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out our YouTube channel for tutorials like this . . .