Our perpetual fears were famously made real in a series of films produced by Universal Pictures. Let’s look at the old school manifestations of our night terrors.

Every year, as the nights get longer, we circle around to our never-quite-forgotten fear of the unknown. What sort of monsters hide in the dark? In cinema, these fears manifest themselves in the Universal Monsters, a series of classic films that were produced by Universal Pictures from the 1930s to the 1950s — the O. G. Cinematic Universe, as it were. They started with Bela Lugosi‘s Dracula and Boris Karloff‘s Frankenstein in 1931. Over the next two and a half decades, the studio would revel in manifesting our terrors on the big screen.

Enter the Mysterious Stranger

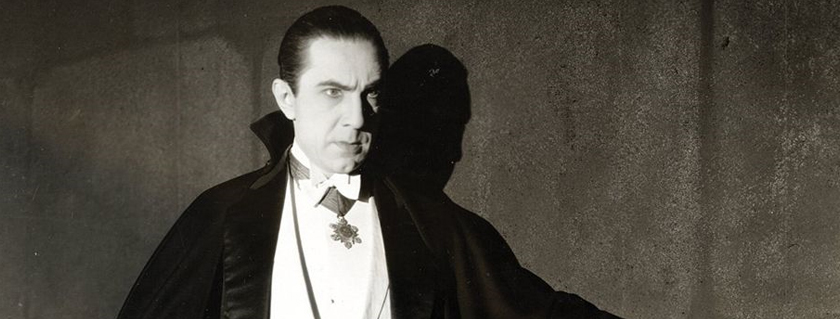

It begins with the classic entrance of the Mysterious Stranger — he of the hypnotic gaze and otherworldly accent. Bram Stoker‘s 1897 novel introduced us to one of the most enduring characters of all time: the blood-sucking Count Dracula.

A displaced foreigner of considerable wealth and means, Dracula is fascinating and alluring when he suddenly appears in society. He disrupts the local community through his esteemed education and poise, his worldly experience, and his magnetic personality. He seduces your daughters and he emasculates your menfolk, both physically and metaphorical, representing a horrifying change to the status quo.

Naturally, a group of townsfolk, led by the quintessential elder (who is, by the way, also an outsider, but whatever), track the Count down and put a stake through his heart, which isn’t a metaphor at all. You’ve got to kill these new ideas dead dead dead.

Dracula had been performed as a stage play dozens of times since its publication, and it wasn’t until 1931 that the eternal bloodsucker found his way to the big screen, where he was played by Hungarian-born actor Bela Lugosi. “Talkies,” movies with sound, were still a novelty in American cinema, as were the idea of “special effects,” and director Tod Browning had to rely on all sorts of sleight-of-hand to produce the effects that we take for granted these days with vampires.

And while his accent was on-point for the Transylvanian Count, Lugosi struggled to find other roles after Dracula. Regardless, the film launched a golden age of horror that would lead to a thousand imitations and revisions. Dracula would show up on-screen more than thirty times over the next hundred years (played notably by Frank Langella and Gary Oldman, for example), as well as appearing countless times across all media. He’s even a breakfast cereal.

There’s a good argument that vampire films, as a whole, hit their peak with Tony Scott‘s too-sexy-for-its-time The Hunger with French icon Catherine Deneuve and otherworldly David Bowie playing the immortal bloodsuckers and a very innocent-eyed Susan Sarandon as the object of their communal obsession. Scott, knowing full well what he’s about to unleash on the psyche of his audiences, puts english Goth band Bauhaus in the opening credits, where Peter Murphy (the living embodiment of Lestat as rock star, frankly) drones on about about Bela Lugosi being dead.

Recently, Anne Rice‘s classic 1976 debut novel Interview With a Vampire has been resurrected on the small screen. Starring Sam Reid and Jacob Anderson, the new series embraces the smoldering sexuality of Rice’s work, igniting a new generation’s fascination with the otherworldly and supernatural.

Blinded by Science

And speaking of transgressions against nature, the same year movie audiences were introduced to the magnetic Count, they met the enigmatic and perpetually misunderstood Frankenstein‘s monster, portrayed by Boris Karloff. Again, as with Dracula, what we remember isn’t the dialogue or the clever plotting but that unmistakable presence and iconic visage.

By this time in his career, Karloff had already appeared in more than eighty films (fourteen in 1931, alone), and for Frankenstein, he is merely billed as “The Monster.” Karloff endured hours in the make-up chair for the role, during which he never imagined that what was essentially a silent part would become the iconic character of his career (which encompassed more than two hundred films).

(Karloff, by the way, narrated the animated version of Dr. Seuss‘s How the Grinch Stole Christmas, a childhood staple for many generations. Won a Grammy for it, too. Now there’s a career trajectory.)

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was written by Mary Shelley and originally published anonymously in 1918. The titular character is Dr. Victor Frankenstein, who, as Shelley references in her subtitle, attempts to reach beyond what is allowed and create something unnatural and extraordinary. Frankenstein’s creation — who is not named explicitly in the text, though the doctor does, in a fit of scientific narcissism and enormous ego, attempt to call it “Adam” — is a fabricated being, born from alchemy and experimentation. Naturally, the doctor immediately regrets his transgression and attempts to undo what he has done. The creature is a little put off by being rejected, and his desperate plea that the doctor make him a companion goes unheard. Eventually, the creature decides that if he is going to be rebuked and reviled, he’ll play that role.

In the novel (which is widely considered to be the first science fiction novel), the monster is quite articulate. He speaks several languages and is well-read. In the film, however, he’s a bestial monster who clonks across the screen and makes inarticulate noises of rage and frustration, a counterpoint to the the urbane and sophisticated Transylvanian Count. And while Dracula is symbolic of our fear of the Other — the stranger who will upset our staid and rigid society — Frankenstein’s Monster is symbolic of our fear of what happens when we overreach. We aren’t supposed to play at being God.

A Love Eternal

Dracula and Frankenstein were immediate successes for Universal, and studio heads fervently scrambled to put Lugosi and Karloff on-screen in as many ways as possible. Fairly quickly, however, the studio realized that what audiences wanted was iterations of these actors’ iconic characters, which is what spawned an eternal cycle of sequels (a necessary aspect of any cinematic universe, unfortunately), as well as a new entry into the canon: The Mummy.

It had barely been ten years since Howard Carter had opened Tutankhamun‘s tomb, and there was still a fervor for all things Egyptian. Writers were tasked with finding a book that they could use as a basis for a new film, and while they weren’t successful (though they did glean some ideas from a short story written by Arthur Conan Doyle), they did stumble upon the lurid history surrounding Count Alessandro di Cagliostro, an 18th-century Italian adventurer and occultist.

Cagliostro, as the stories go, was actually three thousand years old, and from this, the writers concocted the idea of resurrecting an ancient Egyptian ruler (“What if, like, science created Dracula?”). In The Mummy, after accidentally being brought back to life, the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Imhotep (played by Boris Karloff) undertakes a quest to find his eternal love, who he believes has been reincarnated in the modern world (“And what if we bumped up the love story angle of Frankenstein to, you know, get more cross-market appeal?”). And while The Mummy wasn’t as much of a success as Dracula or Frankenstein, it clearly refined the formula that would endure almost as long as Imhotep’s love for Ankh-esen-amun: monsters are sexy, as long as they’re doing it for love.

(See Tony Scott’s The Hunger, yet again.)

It’s not until the end of the twentieth-century with Stephen Sommers‘s reboot that the narrative framework of The Mummy really comes into its own. While the Aged Immortal Seeking Eternal Love plot drives the film, it’s the mix of Indiana Jones adventure and The Thin Man style romantic comedy that fully fleshes out this shambling skeleton. Which is how we got The Rock, by the way, in case you were wondering: Boris Karloff as lovestruck immortal plus Brendan Fraser as goofy leading man equals Dwayne Johnson.

Hairy on the Inside

If Dracula, Frankenstein’s Monster, and the Mummy are all externalized monsters, then where are the internalized monsters? Where are the monsters within? The strange creatures of the unconscious? Well, they were waiting for make-up effects to catch up.

Universal did a werewolf movie in 1935 (titled Werewolf of London), but due to a lack of transformative make-up effects, it came off as a pale imitation of a rival studio’s production of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. It wasn’t until 1941 that Jack Pierce (the make-up wizard who was also responsible for Karloff’s transformation into Frankenstein’s Monster) was able to convince Lon Chaney Jr. to sit for six hours to get turned into the Wolf-Man.

Unlike the other Universal Monsters, the mythology behind the monster isn’t very clear. Don’t get bitten by a wolf. Recite a magic poem. Stay off the moors. The rules keep changing. Well, except for one: beware the moon, because it is under the light of the full moon that the man will be transformed into beast.

While it can be difficult to be frightened of a man with hair glued all over his face, the werewolf is the most insidious of the Universal Monsters.

You can keep Dracula at bay with garlic and a cross, Frankenstein’s Monster is easily recognized, you can stop Imhotep by not opening his tomb. But the werewolf? He can be anyone. He can be inside the house right now. Audiences were pretty good at knowing villains on sight (the Nazis were all over the news at the time, after all), and the Wolf-Man brought an extra chill to the theaters by being “normal” until it was too late.

World Gone Wild

The final classic character in the Universal stable is the Creature from the Black Lagoon, who didn’t debut in the Universal canon until 1954. This film is more than a little indebted to Beauty and the Beast, an 18th century fairy tale that mashes up the idea of the Outsider and the Innocent Sacrifice. However, unlike Frankenstein’s Monster, the Creature from the Black Lagoon is not willing to wait for science to build him a bride.

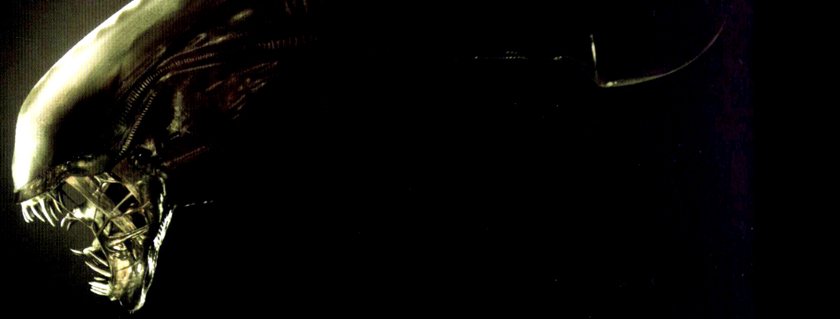

Gill-man takes what he wants because he owes human society nothing. In a world that has recently survived a world war and witnessed the splitting of the atom, the Creature from the Black Lagoon spoke to our nascent fear: the arrival of something truly alien and monstrous that cannot be reasoned with.

You can draw a straight line from The Creature From the Black Lagoon to Alien. Ridley Scott and the creature effects team took one look at the stuntman in the Alien suit and both thought, “Well, we’re not remaking The Creature From the Black Lagoon.” They proceeded to terrify a modern audience by not showing us the monster. It was still there, though. Implacable, incommunicative, and utterly without remorse. Even worse, the Alien didn’t want our women; it wanted to use our bodies as meat sacks to feed its babies. Hello, body horror.

The Universal Five

The Universal Monsters emerged during the Great Depression. At a time when the American people were struggling to reconcile the ideas of American exceptionalism and self-reliance with the simple fact that no one could afford food or clothing, the movies offered them a much-needed escape. We wanted to see our fears and our frustrations made manifest and then defeated, thereby giving us hope and a way forward. Universal Pictures built a cinematic universe around foundational fears of their audience and created an enduring legacy that is still in play today. You’ve got to face your fears in order to understand them, after all. That is why we love our monsters.

Cover image via Universal.

Looking for some music for your projects? At Videvo, our library has everything from free ambient music to music for streams — perfect for any indie project:

- Royalty-free Christmas music

- Royalty-free meditation music

- Royalty-free upbeat music

- Royalty-free jazz music

- Royalty-free Halloween music

Need a break? Check out our videvoscapes — the ultimate reels for relaxation or concentration. Each videvoscape collects hours of high-definition nature footage and background video with downtempo chill beats for the ultimate escape from the grind.